Joan La Barbara will turn 70 years old in June, but shows no signs of slowing down. As a groundbreaking virtuoso performer, she has collaborated with composers such as John Cage, Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley, and Morton Feldman. She has premiered innumerable works for voice, and has proved to be a trailblazer in the realm of extended technique, defying the constraints of language as she communicates with vocal acrobatics that include multiphonics, circular singing, ululation, and glottal clicks. She is also an established composer in her own right, having composed dozens of pieces for voice, chamber ensemble, electronics, chorus, and orchestra.

La Barbara will premiere her new song cycle, The Wanderlusting of Joseph C., at Roulette in Brooklyn on May 24. The song cycle breaks with La Barbara’s usual style of vocal abstractions and moves firmly into the realm of language. For the piece, La Barbara worked with novelist Monique Truong, with whom she also collaborated this past year on A Murmuration for Chibok, a choral work written in honor of the nearly 300 Nigerian girls kidnapped from the Government Secondary School in 2014, 113 of whom are still missing.

THE LOG JOURNAL: Can you talk a little about this new departure from your usual vocal abstractions, and explain how and why you made this switch to language?

So first of all, this work isn’t an opera, but may be the prequel to an opera. At the moment it’s a song cycle. I’ve had an opera in mind for some time. I’ve been working on it since about 2003 and initially it started out as a work about the life and work of Virginia Woolf, but over the years I began to get more interested in the life and work of Joseph Cornell, the marvelous American filmmaker, sculptor, and visual artist. So this song cycle is inspired by the life of Joseph Cornell.

As far as getting into words, I started out in the beginning of my career involved a lot more with sort of traditional singing and art song and opera. At a certain point I began to experiment with the voice, and went with my work quite far in that direction. The works that people have written for me, well, some have words and some don’t have words. What fascinated me and what continues to fascinate me is how expressive the voice is without words. So when you add the words back in, it doubles the effectiveness of what you’re dealing with.

When I started working on the opera, I started doing the libretto myself, but ran into some difficulties, so put it aside for awhile. Then I met the novelist Monique Truong, and I read her novel The Book of Salt. And I found that the way she drew her characters was so rich and compelling and emotionally weighted that I knew that she could write a wonderful libretto for an opera. What I’ve found as I work with her words is that the melodies are pouring out of me, inspired by her beautiful texts.

I’m very excited about this change, and think it will surprise people. But I also have three marvelous singers I’m working with, and I’m inspired by their voices as well. So what I’m doing for Wednesday is what I call a sonic atmosphere. It’s a compilation of about 13 years of work with my ensemble, and I’ve created a collage of these materials inspired by Cornell and Woolf.

Joan La Barbara in Zurich, Oct. 2016

Photograph: Toni Higgins

What do you mean when you refer to this as a prequel?

What I’m hoping is that, with this song cycle, I can perhaps interest someone in moving forward and commissioning an opera. One of the questions that people have faced with my work is that, well, it’s great, it’s wonderful, it’s legendary, but how is she going to do it for other singers? What this work demonstrates is certainly that I can write for traditional singers and that I can also orchestrate.

That would be such a great possibility… especially considering all of the issues that have come up recently, with the Met Opera finally programming an opera by a woman.

I think that the Met thing is really outrageous. And they also haven’t had a woman conductor. They had a kind of two-for-one, where they got a woman conductor, Susanna Mälkki, to conduct Kaija Saariaho’s opera, almost like they were trying to make amends. And the opera already had a great track record, so there were no real chances taken with that.

I think the other thing that’s egregious about the Met is that they decided to nurture a group of young composers — all of them young males.

I’m wondering about your compositional process, which you have described as a “list-making process.”

When I begin work on a new piece, whether I have a concept or a title — whatever it may be — I just start writing stream-of-conscious, and let the words tumble out. Then when I feel like I’ve done a total brain dump, I go back and find where the music is. And invariably ideas will start coming from the words.

When I was in college I was dually enrolled in the music department and the English department, because I did a lot of poetry and creative writing. So, words are very much a part of my background and part of the way I think.

Even when you’re composing something that doesn’t use language in the traditional sense, i.e. asemantic vocal sounds?

I use words in very much the same way that I use visual art. I’m also very inspired by paintings. I’ve written works that are inspired by paintings by Klee and Rothko. So I’m not exactly translating, but it’s a way of saying “here’s what these paintings sound like to me, inside my mind.” So when I go from the lists, I’ll come across a word or a collection of words and they will inspire sound in the same way that the paintings inspire sound.

And as I said earlier, the voice is an incredibly expressive instrument without words. If you just emit sound, it speaks very directly to other human beings. In some ways, to use wordless sound communicates beyond language, and you don’t have to have things translated. If you’re working with sound, it is what it is. We can all have interpretations of what that sound is to us. A lot of people have visual images, or emotional images, or stories that come out. That’s really fascinating to me.

If this song cycle were to transform into an opera, how do you envision the visual and gestural communication playing out?

The way that Monique and I are connecting Joseph Cornell and Virginia Woolf (who never met) is in the reflection of each of their lives. Each of them lost a parent at the age of 13. (Joseph lost his father; Virginia’s mother died.) And each of them went through traumatic feelings about that loss.

What we’ve created is an imaginary water wall between the two lives. When we first see Virginia, she’s lurching out of the water and then tosses the rocks [that she had used to commit suicide] back into it. So essentially what we have is her mind — her afterlife, her spirit. Another thing that Monique and I have talked about is having the scenes somehow folding themselves into a Cornell box.

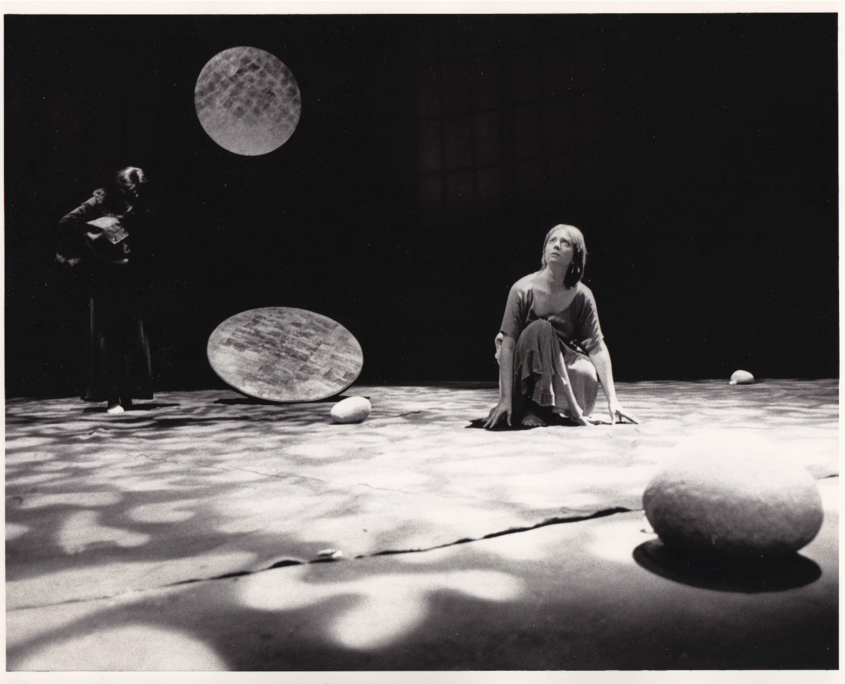

Joan La Barbara performing her work “Winds of the Canyon” at Los Angeles Theatre Center (March 1986), with set by Lita Albuquerque (left).

Photograph: Debbie Richardson

On a more practical note, I’m wondering how your experiences as a performer have informed aspects of your compositional process like notation and performance practice.

I was trained as a classical singer, so I know a great deal about classical technique as well as the way I put my technique to use in more abstract ways. As far as the “composer” aspect of things, I started out composing and improvising, and then began creating graphic scores. In recent years I have combined graphic and traditional notation. For the most part, in this song cycle, everything is notated. (It takes a lot of time — I’m still orchestrating!)

Do you have any anecdotes or advice regarding gendered obstacles in the new music scene?

Hmm. That’s a loaded question. The only thing I can say is, as you’re starting out, it’s an uphill battle. First you have to get your presence, your name, what you do into the arena. One of the problems with contemporary music is that in many cases a work gets performed once, maybe twice — and then nothing.

As far as the gender issue is concerned, specifically in the case of women feeling like they are not taken seriously in rehearsals, my advice is to go into the rehearsal very well-prepared. And if they start asking questions that you feel are demeaning, you need to come right back and establish that you are serious, that you know what you want to do and what you have in mind. Don’t let that attitude overwhelm you.

We saw it so much in the last election. The misogyny. The dismissing of women. By women. It’s a really frightening, inexplicable thing, and there seems to be a kind of acceptance of this attitude. So the best thing that I can say is to do your work, just keep doing your work — which is something that John Cage said to me many many years ago. He said, “Don’t be concerned if you do your work and they laugh at you. Just keep doing it.”

Joan La Barbara will present the world premiere of The Wanderlusting of Joseph C. on May 24 at 8pm at Roulette; www.roulette.org

===

Rebecca Lentjes is a writer and feminist activist based in NYC. Her work has appeared in VAN Magazine, Music & Literature, Sounding Out!, TEMPO, and I Care If You Listen. By day she studies ethnomusicology as a doctoral student at Stony Brook University and works as an assistant editor at RILM Abstracts of Music Literature; by night she hatches schemes to dismantle the patriarchy.