Editor’s Note: The following article concerns a March 19 concert postponed indefinitely because of precautions related to the current COVID-19 health crisis. National Sawdust Log is sharing it now as a gesture of appreciation toward the artists, writer, and readers involved—and, hopefully, as a means by which to express faith in the regenerative and rejuvenating powers of creative arts. We will share news of rescheduled events when circumstances allow it.

Kinds of Kings, a U.S.-based composer collective, continue their National Sawdust residency with a program titled “Equilibrium and Disturbance,” which will feature two new works: Seven Sermons to the Dead, by collective co-founder Gemma Peacocke, and hometown, by Cassie Wieland—a fast-rising composer named one of the collective’s inaugural Bouman Fellows. Both pieces make prominent use of National Sawdust’s new Meyer Sound Constellation system and Spacemap component, which provide the capability both to change the ambient resonance of a room, and also to make sound travel across the walls. This unique technology essentially acts as another musical instrument in a composer’s palette.

The theme for the upcoming concert, and the Kinds of Kings residency as a whole, is an ecological concept. In nature, predators eat prey—and even if they eat too much, nature finds a way to come back to equilibrium. “For this residency, we wanted to push the boundaries around who comes to new music shows,” Peacocke explains. “The idea is that we would disturb some of the norms that happen in new music and classical music in New York, and that hopefully things will be disturbed enough to shift the whole system a little. It always returns to equilibrium, but hopefully not the exact same state that it was in before.”

Her new piece, Seven Sermons to the Dead, is inspired by the philosopher and psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s illuminated manuscript, The Red Book. Encountered by Peacocke via a Wikipedia rabbit hole, the manuscript details Jung’s willful hallucinations, including one in which many ghosts and spirits were packed tightly in his house, all the way to his front door.

“I’ve written so much melancholy music, and I wanted to try to write something that was kind of spooky and scary, and also a little bit campy or fun,” Peacocke explains. Using the Meyer Sound system and visual projections by artist Xuan, she wants to create an immersion. She describes the sound of the electronics as “ghosts whooshing around the room,” while visual apparitions appear in a smoky atmosphere.

Both Peacocke and Wieland are among the first composers to write music specifically for the Meyer Sound system, which they’ve described as an exciting challenge. “There’s a lot of imagination in it,” Peacocke says. “The most complicated part was splitting the electronics that are in the tape part into multiple channels, and then putting the right sounds and the right motifs into the correct channel. And, of course, you don’t have the National Sawdust venue with you at all times, so you need to imagine how the placement of the sound will feel performed in the space.”

Since the fall, Peacocke and Wieland been working with the National Sawdust tech team to learn how to use the sound system. Interviewed for National Sawdust Log, Wieland – a sound engineer herself, in addition to her work as a composer – explains a bit more about her piece and the process of bringing it to life.

Cassie Wieland

Photograph: Emma O’Halloran

VANESSA AGUE: On March 19, you have a new piece premiering. What’s the title, and what was your inspiration?

CASSIE WIELAND: It’s called hometown. It was written for Izzy O’Connell, the amazing pianist who will be premiering the piece, and Adam Holmes on percussion. It’s written for National Sawdust’s brand new Constellation and Spacemap system. The inspiration behind the piece is actually my hometown: I grew up in a town called Normal, Illinois. I didn’t even think it was funny until I moved somewhere else and people asked, “It’s called Normal?” I guess I didn’t think about that before.

It’s safe to say that Normal is different from Brooklyn in every way imaginable. I wouldn’t call it rural per se, but it’s very flat, with big open skies. At any given point you could see about two miles in the distance. This piece is inspired not only by the geography of Normal, but also the idea of nostalgia and the complex feelings that can arise from that. At times I’m very nostalgic, not even just for the people or experiences that I had, but the location of my hometown. And, oftentimes there are a lot of feelings that go behind that, too. With nostalgia, you can have this weird yearning, but at the same time know that it’s not a good fit for you in the present. My piece is inspired by that concept. And it’s a very textual work, so I tried to bring out not only the vastness of the geography, but everything that’s mixed up with feelings about my childhood and the place I grew up in.

AGUE: This idea of displacement, or moving on, is something that’s also come up in your work before with Weeds and in a (once-)blossomed place, the EP that you released last summer. What draws you to that concept?

WIELAND: That idea of displacement and thinking about your environment as a part of you has come up in my life a lot, personally, and it’s something that has definitely shaped my perspective and goals as an artist. It’s something I’m fascinated by, because everybody has experienced it. Everybody has gone to a new place and felt some complex feelings about it, or that they don’t belong. By looking at it and talking about it, it helps me to process my own feelings. These past two years have been the first time that I’ve ever moved out of Illinois, away from home. It’s helping me process my feelings about that, as an adult and as an artist. It’s something I’d like to discuss, because I feel like talking about that idea will bring other people together too, which is ultimately one of my goals as somebody who makes music.

AGUE: This is coming from a really personal place for you. How does writing something that personal effect you? What are you looking to do with bringing your personal experiences into music?

WIELAND: My writing hasn’t always been personal. Especially during school, as I was learning to compose, I got a vibe from the classical music world that writing is more or less an intellectual act. Nobody outright told me this, but there is a vibe that because it’s such an intellectual act; it’s not about you, it’s about bigger matters. Bigger matters than yourself, bigger matters than your own feelings. But as I’ve been writing more and more, I’ve been thinking and realizing that the personal little deals are big deals. The personal can affect somebody just as much as a big cultural matter. I grew up on Midwest emo, math rock, and singer-songwriter things, and a lot of the music that I still listen to is about personal things. If I love this music so much, why not incorporate it into my own perspective, too? I’ve definitely been gearing more towards personal matters, because that feels more honest to me as an artist.

Now that I’m branching out into this topic that feels more honest to me, I’m trying to find the line between opening up and not just completely spilling my guts out on the floor and inviting the audience to just have at it. I don’t want to barge into the concert hall and say, “Guess how bad my day was today.” I’m really trying to find those small and intimate and special things that can also be intimate and special to other people.

AGUE: hometown uses electronics. We’re talking a lot about how you’re writing about a personal experience, but so much of the time we think about electronics as very impersonal. How are you thinking about blending these two ideas, the impersonal and the personal?

WIELAND: One reason I love working with electronics so much is that you have the opportunity to create an environment for the listener, for the musicians playing. That’s really how I’m thinking of these electronics—I don’t see the use of electronics as machine-like at all. I just see them as a tool to create an environment. Actually, all of the sounds that you’ll hear in my electronic tracks are mostly acoustic sounds, just manipulated. The first movement is all granulated vibraphone samples that come out of the same vibraphone that Adam will be playing, and there’s a little bit of synthy stuff behind that that I added. The second movement is all processed sounds of my voice, mixed through or sent through vocoders and a lot of auto tune. I see electronics as a production tool to be able to create. For me, the backing tracks are how I imagine the musicians are feeling, or how I want the audience to feel.

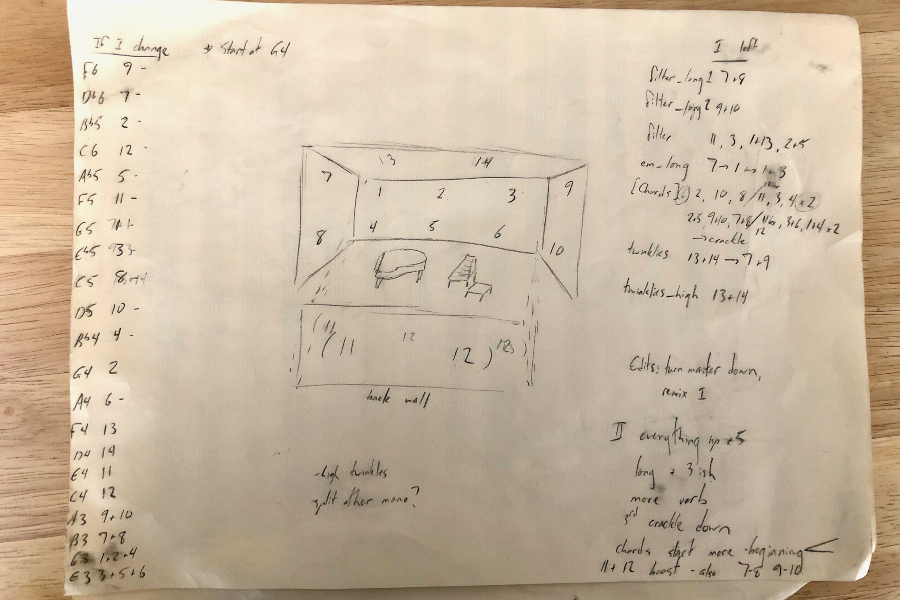

Cassie Wieland’s pencil-plotted “space map” for ‘hometown’

Photograph: Cassie Wieland

AGUE: I can imagine you could create a lot of moods in the National Sawdust space with the Meyer Sound system. This system is really complex to use—we’re talking tons of channels. You can do pretty much whatever you’d want with sound. How did you start thinking about writing for something like that?

WIELAND: I’m not going to lie to you: I was overwhelmed at first. I’ve never worked with something as complex and freeing as the Meyer Constellation and Spacemap systems. Obviously it’s a very special system that not a lot of people get to work with. But before I had any idea of what I was going to do with the system, the National Sawdust tech team was nice enough to invite us into the space, and Garth MacAleavey and Charles Hagaman led a demo of what the systems can do, how they function, and how they’re manipulated. Just being able to sit in the space and hear what was going to happen was really beneficial, especially because it’s not very often that you get to think about your music in the context of a specific space. That was really, really exciting, and helpful.

What I ended up doing is mapping out “stationary channels” that I place throughout the space. Each of those channels has an individual input. If you hear sounds moving around, that’s because all of them have their own audio track, and I manually moved sounds from one channel to another in the designing and mixing before they even got to the space. That’s how that works. It’s really hard to get work done when you don’t have a surround-sound system in your home, just because of the pure physics. If you’re working on your laptop or home speakers or headphones, that’s only two channels, a left and a right. You can pan things to be more in the left channel or more in the right channel, but it’s still just two. Over a lot of trial and error, I’ve learned how to mix 14 channels on my laptop instead of two without blowing up my computer. So that’s been great.

AGUE: So you’re using 14 channels for this piece?

WIELAND: Yes, I’ve got six on the front wall, two vertically stacked on each side, two in the back, and then two in the ceiling.

AGUE: When you were writing this at home, you had to do a lot of imagining. What is the difference between what you’ve come up with in your head versus what you heard standing in the space?

WIELAND: What I imagined would happen versus what actually happened when we had our first tech rehearsal is actually very similar to if I were writing for an acoustic instrument. It’s always crazy to see what actually comes of what you’re writing down or what you’re mixing in a laptop because, in some ways, you listen and you think, “oh, this is way better than I thought it was going to be.” But no matter what, it’s going to sound more real, and that’s always a humbling experience. It’s not going to be as terrible as you think it is and it’s not going to be as magical as you think it is, either. But I’m so happy that the tech team is being so generous with letting us do these tech rehearsals, because it’s really only when you get into the space that you know what needs to be done.

AGUE: You have a whole career doing sound engineering. How is that playing into this piece? Do you feel like that informs your knowledge for writing it?

WIELAND: Maybe not so much in writing it as in the stuff that happens after the writing, like thinking about the logistics and how the musicians are going to make the sounds or control the electronics and what extra equipment I want to use, if any, or what amounts of reverb or spatialization to use. I have a way better grasp on than I initially thought I would, just because I do this for other people all the time.

AGUE: Now you get to do it for yourself! Is there anything else that you would like to add about writing the piece?

WIELAND: I’m very excited to be able to do a concert that’s special in this way, where this piece was made for very specific people for a very specific space. While I was writing it, I had those people and that space in mind. It’s going to be accompanied by beautiful projections by Xuan, too, whose work I love. So to be able to collaborate with all these people, and to really just make one special moment out of it, is super exciting to me.

Performances by Kinds of Kings and Cassie Wieland will be rescheduled when circumstances allow it; please stay tuned.

Vanessa Ague is a violinist, avid concertgoer, and music blogger at theroadtosound.com, and the development and research associate at National Sawdust. She was a 2019 Bang on a Can Media Fellow, and holds a Bachelor’s Degree from Yale University.